Introduction

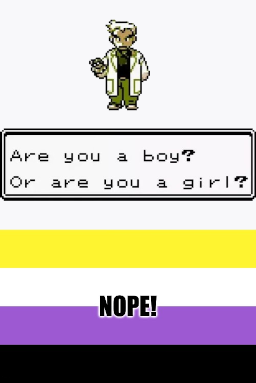

Are you a boy? Or are you a girl?

This quote is from Professor Oak at the beginning of the Pokémon games, as commonly known by most people familiar with internet memes. This phrase has been popular online for over 15 years now1, expressing different waves of attitudes towards gender. At one time, jokes about “checking” what someone’s gender was based on “what was in their pants”, with a creepy uncle vibe, were commonplace in an online culture where the constant harassment and surveillance of women and homosexuals was treated as a joke. Over time, it transitioned towards a phrase of gender questioning, adopted as an in-joke by many transgender people online, demonstrating the confusion that older people like Oak, who can’t even remember their grandson’s name, may have with understanding their gender expression. In a way, this simple question was able to express a larger question surrounding gender - whether it be one that explores the possibilities of what it can be, to those that aim to reinforce strict its binary - through the physical interface of the machine of the Gameboy playing the cartridge.

However, what a lot of people don’t realize about this phrase is that the Professor doesn’t actually ask you this question when the world first played the Pokémon games in the late 1990s. For the player, gender was not a choice in Generation 1, and it was heavily implied through the writing of these games that you are a boy. It was not until Pokémon Crystal Version2, released internationally in 2001, that we had the ability to not only be something besides a boy, but even have the privilege to choose our gender, all through the confines of the interface. This interface of experiencing gender through the literal machine of a physical video game gives the surface to explore not only new possibilities for gender, but how subtle transitions in game and narrative design can dramatically transform what experiences people absorb from it.

To understand how a video game could possibly produce something like “our understanding of gender”, I want to turn to the concept of “subjectivity”. In this case, I am not referring to to the idea of a so-called objective reality being called into question by a purely subjective ontology, or asking for a purely relativistic universe - the acknowledgement of subjectivity and local variables in people’s experience is not a denial of larger macroscopic movements. Rather, it is what is produced at the intersection of a hyper-complex, transversal set of social machines existing in various scales. In The Three Ecologies, written at the tail end of his life, Félix Guattari writes:

The subject is not a straightforward matter; it is not sufficient to think in order to be, as Descartes declares, since all sorts of other ways of existing have already established themselves outside consciousness […]. Rather than speak of the ‘subject’, we should perhaps speak of components of subjectification, each working more or less on its own. This would lead us, necessarily, to re-examine the relation between concepts of the individual and subjectivity, and, above all, to make a clear distinction between the two. Vectors of subjectification do not necessarily pass through the individual, which in reality appears to be something like a ‘terminal’ for processes that involve human groups, socio-economic ensembles, data-processing machines, etc. Therefore, interiority establishes itself at the crossroads of multiple components, each relatively autonomous in relation to the other, and, if need be, in open conflict.3

In other words, to understand how the gendered subject emerges in Pokémon, it’s not merely an analysis of just how gender exists in Pokémon, but also how it is produced by everything ranging from the narratives of the Pokémon franchise, consisting of many moving parts such as the games, cards and anime, to the way its narratives were constructed, and the very structure of the code itself producing what is and is not possible in the games regarding gender, and how these “machines” interact with each other to produce new possibilities outside of the expectations of the developers. With that all in mind, perhaps Professor Oak has every right to be confused!

Assigned Male

To understand part of the wave that encompassed the world for years after the release of the media sensation Pokémon, it helps to analyze a single unit of the machine that manufactured the way to understand being a “Pokémon Master” - that is, the games themselves. These games are a part of the mass produced subjectivity producing machines within the franchise. The video game machine mass production machine produces code that can be stored on physical cartridges that can be mass produced on huge scales in factories that is executed by the Game Boy’s processor to have its contents spilled across the Gameboy’s memory. The way that this machine produces sounds and images to construct narrative structures in players minds is essential to this phenomenon, since it is where the junction of social, mechanical, psychological and ecological machines is ultimately seated - the interface between the eyes and ears of the player, and the speaker and screen of the console. This feedback machine continuously generates the Pokémon world through a process of desiring-production, a process where players encode their desires through the physical game by hammering away on the buttons to produce narratives looped back to the player - as observed not just in the games, but the entire social territory it occupies. The worlds implanted upon by these machines onto the players then could be repeated in the social sphere, by talking about the Pokémon world as if it occupies some real world presence - not necessarily that Pokémon are real, but rather that the media reality of Pokémon exists in some sense and is accessible through the physical media of the franchise - like a connection to a new world, the Pokémon world. It’s through this process that positions the Pokémon World somehow in physical reality, allowing us to occupy our real world lived lives with its affairs, and mobilizes it for its cycle of capitalist 90’s media hyperconsumption where all its surplus capital can be funneled back to the IP’s owners.

When children booted up these games after receiving it for their birthdays, Christmas or whatever other occasion, they were met with two choices presented by Professor Oak at the interface in the beginning of the game. Not name and gender - but rather, your name and your rival’s name. As it turns out, Professor Oak was very poor at remembering these kinds of details, especially with his advancing age, and so he had forgotten his grandson’s name. You deviously name him whatever you desire, forcing your rival into a bitter position where he is constantly misnamed by his own grandfather, fueling the rivalry even further. But there is no mention of gender. Why should there be? It is not that your gender is ambiguous, or left up to chance - but is explicitly assigned male. Narrative and UI choices make this explicitly clear. Default names like Satoshi and Jack emphasize that your character is male, and the character’s sprite is that of what appears to be a boy. By the time you reach Erika’s gym, it is confirmed unquestionably that you are a boy, because the trainers in the gym question why you are there when it is an all-girl gym, and even express concern for you being a peeping tom - a problem the gym suffers through constantly, with a creepy man stationed outside the gym peeking in for the player to encounter!

Because of this assigned gender, while male players could play these games with the character as a direct relation to themselves, female players were left with being forced into the body of a male in the Pokémon world, at least in the game boy. It’s not that the concept of a female Pokémon trainer does not exist in this universe, but that it is structurally inaccessible to the player. As a result, all female players are masculinized through this process - in a way, femininity is flattened, because masculinity represents the core playable subject, the “default” human being - and the female is always relegated to the real of perpetually being outside of the player’s grasp. This lead to female players at this time to separate their subject as a trainer into two, disconnected halves - the subjectivity of the character produced by the user interface - a male - and their body in relation to other real world Pokémon fans - a female - forcing female players into a bigendered role, a role that exists outside of the gender binary, but still strictly within it. Through forcing female players to submit unconditionally to the experience of being forced into a new gendered cage while men are free to express themselves as they see themselves, they simultaneously both deconstruct the real world gender binary by producing boys who are really actually girls, while also being reinforced into it through using the strict gender assignment to reproduce masculinity as seen in life.

Furthermore, as a consequence of being assigned male, the relationship between you and your rival is homosexual - not in the sense necessarily that they are gay for each other, since after all they are young, prepubescent boys - but rather that their gendered dynamic relies heavily on their same-sexed orientation. The rivalry is constructed in such a way that there can only be one Pokémon League champion, so they continue to funnel their desire into their relationship to each other, ignorant of the complex political relationships between the Pokémon League, hypercapitalist enterprises like Silph Co. and Team Rocket. Like a machine of two binary stars’ gravitational pull plummeting themselves one into the other, their aggressive masculine energies accelerate to rapidly produce two of the youngest and most powerful Pokémon trainers to exist, whose combined power acts as a disruptive machine for large-scale political states, such as the criminal and terroristic activities of Team Rocket.

The Pokémon themselves have their gender obscured in most cases, as opposed to being assigned. Unlike the player, they are not explicitly male or female, but simply their gender is not determined. Pokémon in Red, Blue and Yellow have no gender at all, outside of the Nidoran-M and Nidoran-F lines that are explicitly stated to be male or female - a means to try to incorporate sexual dimorphism being used as a gimmick in their design philosophy to separate them from the other creatures that looked the same presumably for both genders. This was reflective of how, for example, in bird watching or herpetology guides, gender can be identified through physical characteristics for some species, but in many species the gender is ambiguous. Despite this, Pokémon gender still sometimes leaks through in minor NPC dialog, such as a woman who asks if male or female Pokémon are stronger, or a man who explicitly states his Machoke is male. While it has no sex in the game’s code, Pokémon like Kangaskhan are coded into feminine roles of matriarchy and motherhood.

Mew is a particularly interesting example, because the diary entries on Pokémon Mansion on Cinnabar Island imply that Mew, the legendary Pokémon that represents the origin of all species, was said to have “given birth” to Mewtwo - its clone. In the French version, the gender is made even less clear - the diary entry asks if Mew is a “Dad” or “Mom”4. In later games, Mew would explictly have an undefined gender, making this relationship between Mew and its child even more interesting, as it breaks down the assumptions of how gender produces the reproduction of life. In a way, by these games exploring themes of cloning, they were exploring the possibility of science to break down the machines of gender completely, removing the need for male or female subjects to reproduce the subject of fertilization within the womb.

A New Era of Gender

Generation 2, consisting of Pokémon Gold and Silver, released a few years later in 1999 in Japan and 2000 in the United States, as well as the later release of Pokémon Crystal, could be called the “Gender Generation”, really with gender being a euphanism for sexuation, or the division of subjects into sexed characteristics. Like Eve being produced from the subject of Adam, the gameplay mechanics evolved to produce completely new relations between gender and Pokémon, as well as later the player themselves. Introduced not only were Pokémon having gender, but also the concept of genderlessness, and even having different ratios of how common each gender was in a species, but also the introduction of Pokémon breeding, with a particular focus on the new concept of “Baby Pokémon”, thus firmly coding a gender binary to regulate reproduction into the literal binary flashed onto the cartridge. In this new ontology produced by these UI machines, male and female Pokémon could come together to produce Pokémon eggs, and allow for the transmission of stats and special moves. This feature would lay the groundwork for a core game loop of the series moving forward, cementing the reality of binary gender into the gameplay discourse of the games.

This structure of male-female relations constructed what can be called a heterosexual normativity in the world of Pokémon, where the functions of male and female play important roles in the reproductive process through their differences, like a key to a lock. Unlike the heterosexual normativity of humans in the real world, where the binary of gender is defined largely through the ability for certain individuals to impregnate others to force them into being part of this reproductive process, Pokémon gender produce a different set of relations. Female Pokémon in a breeding pair designate the species of the child, while male Pokémon designate its moveset. Additionally, Pokémon are restricted to only being able to breed within their corresponding breeding “egg groups”, allowing for bizarre relations between species, whereas in real life reproduction is restricted by chromosomal differences between species. If two Pokémon of the same gender are placed in the daycare, they will not simply not breed, but largely ignore each other entirely. Not only does this indicate to the player if a pairing is incompatible, but it reinforces the heterosexual normativity strictly through the authority of the game’s design. Thus, the gender binary is structurally reproduced through the game’s code as a means to regulate Pokémon reproduction through the player’s control of their bodies, to extract the surplus value of Pokémon breeding - more powerful Pokémon with unique, otherwise unobtainable moves.

As a consequence of trying to reconcile this change alongside cross-compatibility with the gender agnostic world of Pokémon Red, Blue and Yellow, and because there was no special random value to determine unique traits in individuals besides differences in Pokémon statistics, a special stat called the “Attack IV” was used to determine gender. “IV” stands for “Individual Value”, which are values that determine unique variation between stats of individuals of the same species of Pokémon. In these games, Pokémon with a value higher than the cutoff point for the gender ratio were gendered male, while those lower would be female. This unintentionally encoded the reality that female members of a Pokémon species had a lower Attack stat than males, which produces a physical imbalance between the sexes (other traits, like the Unown’s letter value and how “shininess” or alternate coloration is determined, is also predicated on the same system of IVs, leading to other strange, restrictive situations where only specific stats and forms can be shiny). Thus, to support the transition from gender ambiguity to gender binary, an unintentional weakness is introduced into female Pokémon, something that would be corrected in later generations.

Some Pokémon, such as Tauros or Hitmonlee, are always male, while others, such as Chansey or Kangaskhan, are always female. The traits of these mono-gendered Pokémon repeat characteristic stereotypes with each sex - Tauros, Nidoking and the Hitmons all exemplify masculine traits of combat and aggression, while the female Pokémon repeat traits that reinforce their position in feminine roles, such as Chansey and Blissey’s desire to care and heal weakened Pokémon, Milktank’s very prominent udders and Kangaskhan’s maternal roles. One of the most controversial Pokémon card arts ever released was the Japanese art for “Moomoo Milk”, a product produced by miltank, where in the artwork, Sentret is sucking a nipple. This would not be the first time a Pokémon card would be censored for gendered reasons - the Team Rocket release of Grimer in the Japanese version disturbingly depicts this creature peeking up a girl’s skirt.

All of this would make one assume that the gender binary is strictly coded into the Pokémon universe and is an unquestionable word of law, considering that it is literally integrated into the game’s flash ROM. However, this heterosexuality is one that is often broken as one dives deeper into the user interface, game mechanics, code and narrative. Perhaps the most obvious objection to heteronormativity within Pokémon is the existence of genderless species. Unlike human intersex conditions, genderlessness is nearly always associated with sterility - a complete failure to access the reproductive process.

Genderlessness among Pokémon appears to be divided into three categories. The first category are genderless Pokémon such as Magnemite, Staryu or Porygon, who curiously still belong to egg groups despite being genderless. These Pokémon can only breed with the transforming Pokémon Ditto, but are still capable of producing eggs. The second category are Pokémon with the “No Eggs Discovered” group, which are associated with Legendary Pokémon typically - Pokémon that represent forces of nature, supernatural powers or abstract concepts, who exist as the manifestation of abstract entities rather than truly individual members of a species, and thus cannot breed because they are effectively concepts with bodies. Finally the third category is for Ditto, who seems to completely invert the sterility of other genderless Pokémon by being able to become and breed with anything - a Pokémon that, as a result, has been associated both with imagery of gender transition as well as prostitution. Because it always transforms into an exact copy of its target, including its gender, it can only be assumed that all reproduction with Ditto is homosexual and ruptures this heteronormative system of reproduction. One can compare Ditto’s potential ability to become anything - an extension of reproductive possibilities into the future - with Mew’s status as the origin of Pokémon speices - which historicizes all reproduction of Pokémon into the past - both genderless, both bounded with infinite potential.

Likewise, the introduction of choosing your gender in Pokémon Crystal also completely changed the playing field for producing the subjectivity of the player’s gender in the gameplay experience. Unlike the previous games, where not only are you male, but you have no choice in the matter - you have the option to choose a gender, male or female. This opens up unique possibilities for the player to experiment with their expression. No longer do girls have to present themselves as men to be players in the Pokémon universe, but an even more exciting possibility opens up - the possibility that boys no longer have to be boys. Suddenly, there was no forced binding either sex between the user interface and the body of the player, allowing for gender experimentation to freely begin.

In contrast, the story, to allow for the choice of free gender, becomes noticably more degendered and deterritorializing - or in other words, breaking down the social territories of - the boundary between what is male and what is female in the Pokémon franchise. This deterritorializing effect is recaptured back into the user interface by still requiring a player to select their gender and by visually reinforcing through character design certain sexed traits that associate gender identity and role with bodily characteristics - but the choice allows what body can be chosen, thus unlocking new potential futures. This deterritorialized gender even appears to have somewhat coded the appearance of the rival, Silver, by giving him longer hair and a more androgynous appearance. Alongside his more gender-ambiguous look, he also exhibits a much more morally ambiguous position - not aligned with either Team Rocket or the player, as he commits crimes as an independent rogue with unclear motives to organized society. In a way, similar to how he steals the Pokémon from Professor Elm early in the game, he also steals some stereotypical qualities of feminine beauty for himself, and both his appearance and his intentions become more complex, blended and grey. He is not merely a male who identifies as female, but a man that subtly transgresses social gendered categories through molecular becomings.

Even the production of the video game’s codebase itself is not immune to this deterritorializing effect. One may think that because the video game is a strict set of flows and pathways determined by the developers, that breaking free from a designated hard-coded gender binary is impossible. However, as the previous generation’s games demonstrated with its slew of unstable schizophrenic behaviors through glitches like Missingno. and the Mew Glitch, the intentions of developers and what is actually produced by the machine are two very different things. While these new games were considerably more stable, now that Nintendo recognized the value of the franchise, they encouraged more stable development patterns with significant corporate interference and attempting to repress the possible chaos that could be released from another Missingno.-like glitch, that does not mean that the game was immune to bugs. One area that seems to have been undertested by quality assurance were the special Pokéballs that were obtainable in Azalea Town. These balls are notorious for having bugs, but perhaps one of the most amusing is the Love Ball. This ball is supposed to have a higher catch rate if your Pokémon has a different gender than the wild Pokémon, however, due to a bug, it was coded to instead work on the same sex. Through this simple error, it demonstrates how the unconscious desire that produced the code tries to break free from the constraints of a gender binary can find a line of flight through even the slip of a finger while typing to produce a homosexual becoming, thus allowing the player “to look for what is homosexual, […] even if [it] is in other respects heterosexual” - as Guattari suggested in an a 1979 interview5.

The Evolution of Gender in the Pokémon Franchise

As the Pokémon franchise developed into its more modern incarnations from its humble beginnings, the development process of the games became more organized, more designed around the desires of Nintendo, CREATURES inc. and The Pokémon Company, as opposed to the more innocent experimentation of the original Pokémon development within GAME FREAK in the early 1990’s. The games had produced a media ecosystem that, in order to maintain its existential territory and health in the marketplace, required internal corporate management and regulatory structure, that found itself producing more stable codes. For example, in Pokémon Ruby and Sapphire at the beginning of Generation 3 to prevent interaction with the previous more unstable titles, as well as to improve internal design and prevent hacking Pokémon to encourage a future competitive ecosystem and the hosting of official tournaments, Pokémon data was completely reorganized to plug these creatures and their world into a continuous money printing engine that could coordinate its efforts with other media in the franchise for as long as Nintendo could push on for.

In these new games, the data structure of a Pokémon was split into 4 sections. These sections would be organized differently dependent on the result of a checksum, meaning that the position of where certain Pokémon data was, was dependent on the data of the Pokémon itself - as an attempt to prevent players from hacking their Pokémon. Doing so incorrectly would transform their Pokémon into a “Bad EGG”, an unusable Pokémon that forcibly takes up space in your boxes to punish the player for hacking and violating this structuralism. Part of this restructuring was the addition of a new special value, called a “personality value”, that would separate gender from battle-relevant statistics, along with other unique traits such as shininess, abilities, nature, the evolution path of Wurmple, or the spots of Spinda and other mechanics. This personality value would thus fence the concept of male and female Pokémon purely within their reproductive capabilities, and some secondary special heterosexual mechanics such as the move Attract or Cute Charm. This “personality value” could almost be considered a binary mask that codes the uniqueness of ones body.

The narrative control of gender while incorporating and recapturing its possible variation back into a consumerist interface continued into Generation 4, with the introduction of gender differences. This new feature caused the gender binary to evolve once again to produce variation between the genders of various Pokémon and to emphasize their differences. Perhaps most obnoxious was how female Pikachu tails now have a heart on them to signal their femininity - tying the anatomy of a mouse to a symbol that is associated with young girls, that forces them into a world of “love” before they can even understand what their bodies are. Gender differences would evolve even further later with the addition of species like Meowstic and Indeedee, with differences in base stats, abilities and movesets based on their gender - who quite interestingly are both Psychic type Pokémon, almost implying a psychoanalytic gender divide. As the games became more and more corporate pandering, the more the games would control narratives surrounding ambiguous gender, such as how in a Pokémon Sun and Moon player’s guide suggests that genderless Pokémon are merely Pokémon who cannot have their gender reliably identified6, or using Ball Guy’s gender ambiguity as a means to invoke mystery both in the games and in marketing - both toying with the idea of gender but not really disturbing its binary.

Despite these efforts of controlling and regulating gender and recapturing experimental decoded gendered flows and returning them back into the structures of the Pokémon universe, the struggle between the ruptures of new kind of gendered experiences would still emerge through code mistakes and narrative. Famously, Azurill has a different gender ratio to Marill, which resulted in 25% of Azurill changing from a female to male gender in Generations 3-5, and forcing the developers to override this behavior in personality value manually in Generation 6 to prevent this from happening7, ironically in the same generation where the dialog explicitly suggests a random trainer is transgender - thus again overcoding what bodies and uniqueness can really be to fit into a specific gendered paradigm. Personally, I think it would be interesting to have sex-changing Pokémon to reflect unique life cycles in nature such as those with clownfish.

Despite all attempts to contain its power, all of these interactions with gender through the machines of the Pokémon franchise transformed all of those who touched it, ranging from subtle codifications to mass personal revelations among thousands of individuals. Even those working on the production of Pokémon would find themselves transformed by these movements. Maddie Blaustein was an intersex voice actress assigned male at birth who worked with 4Kids on the Pokémon anime, famously providing the iconic voice of Meowth from Team Rocket for most of the show’s 4Kids run. She developed considerably her own struggle with gender by playing the role of Meowth in the episode “Go West Young Meowth”. This episode was about how Meowth, having a crush on another of his species named “Meowzie”, wanted to impress her by becoming like a human through learning how to speak. Unfortunately, Meowth was rejected by her for being “a freak”, and this rejection ultimately lead to him joining Team Rocket, having his new skills be exploited by a larger system. This reflected upon Blaustein, making her see in herself her own desire to change, feeling trapped as a woman in a man’s body, similar to Meowth being a human trapped in a Pokémon’s body.8 Similarly to Meowzie’s reaction to Meowth, transgender people are rejected by non-transgender people often as “freaks” themselves, for breaking through the territorial boundaries assigned to our bodies, finding their unique new position and motion across the body binary being similarly exploited for the extraction of the surplus produced by their unique positional existence through unscrupulous means - typically in the form of sexual exploitation of their bodies while actively suppressing their rights. Tragically, Blaustein passed away young at the age of 48 in 2008, from a battle with an unidentified stomach virus, possibly perpetuated by a loss of job security caused by the firing of the entire 4Kids cast several years earlier.

There is a lot to explore within the anime and its portrayal of gender, but I am less familiar with the anime and needed to constrain my analysis for brevity, but I highly suggest thinking about the interesting expressions of gender between the main gang of Ash, Misty and Brock versus Team Rocket’s weird and queer activities and how they are codified in the Pokémon universe on your next viewing.

Summmary

Pokémon, through its user interfaces, media, narratives and other structuralist machines, combined together in new ways to produce futures that could never have been imagined with gender. New becomings, new worlds, unpredicted, unexplored, came into existence - not because of what these structures told us how things should work, but rather the unenunciated transmisions between them that allowed for the creation of new futures for creatures and the machines of creature-production. Its through these experiences that leaked through the cracks despite the reinforcement of structured codes literally embedded into the ROM chips that allowed for these developments to happen. No matter how hard one tries to force desire into the confines of structure, it always will try to find ways to break free.

Tune in next time for a new Pokémon adventure. Next episode - we will be exploring the existential themes in Pokémon movies and spin off games. Are you ready to become a Pokémon machine master?

-

(Pokémon Crystal Game Script)[https://gamefaqs.gamespot.com/gbc/198308-pokemon-gold-version/faqs/49457] ↩

-

Félix Guattari, “The Three Ecologies”, pg. 36 ↩

-

Félix Guattari, “Soft Subversions”, pg. 149 ↩

-

Pokémon Sun & Pokémon Moon: The Official Strategy Guide, p. 288; Sourced from Bulbapedia’s article on Gender Unknown ↩

-

The Inspiring Story of the Trans Actress Behind Your Favorite Pokémon’s Voice ↩

posted on 06:44:05 AM, 01/23/25 filed under: gender game theory [top] [newer] | [older]